Review: Bird’s Eye View

As promised, another excellent review from Martyn:

Review: Elinor Florence (2014) Bird’s Eye View; Dundurn Press, Toronto.

For me, successfully reading a novel requires a considerable degree of immersion, which means ideally being able to sit for at least an hour or two without interruption (yes, they know who they are and they will be made aware of this post). But it isn’t just pets and children and just about everyone else that can disrupt proceedings – there is also the problem of a little too much prior knowledge about the subject matter.

As an archaeologist, I first experienced this when reading Peter Ackroyd’s novel First Light back in the early 1990s while camping near Carnac, which is a piece of irrelevant detail. Everything was fine until the archaeological side of the story came more to the fore… An Early Bronze Age leaf-shaped sword? In Britain? No! Absolutely not!! And no way is that an appropriate excavation strategy for a long barrow. Yanked straight out of the narrative, I found myself back at the campsite wondering what other paperbacks might be skulking unclaimed in the tent [i]. The experience didn’t just overshadow the rest of the book (yes, I did finish it), but also made me a little wary about some of Ackroyd’s subsequent novels –I even found myself doubting that 17th century poet John Milton had ever really crossed the Atlantic. It takes a lot more for this sort of thing to happen these days – working for Historic England, prolonged and disciplined suspension of disbelief is an essential daily requirement.

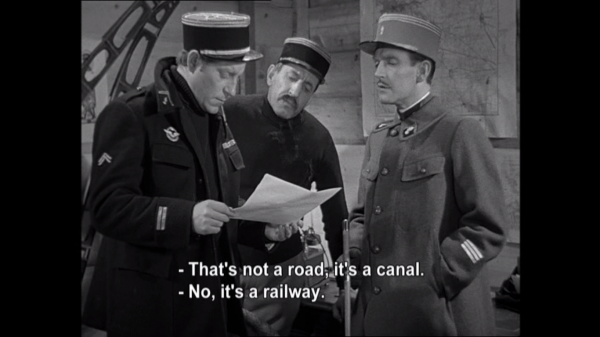

Fiction involving air photo intelligence isn’t exactly common. When it does crop up, it is usually presented as something relatively straightforward and unproblematic, as in a lot of archaeological reports. After all, understanding what’s on a photo can’t be that difficult, can it? There is the odd exception though. My favourite example occurs in Jean Renoir’s 1937 film La Grande Illusion [ii]. In an early scene, French aviators disagree over what they see on an aerial photograph. In the next scene we watch two of them being led into a PoW camp, having been shot down and captured by the Germans.

Qu’est-ce que c’est? Air photo interpretation from La Grande Illusion. The feature of interest was actually some indistinct smudge obscured by the more easily identifiable road or canal or railway or whatever.

So, when I heard about a novel set in the world of air photo intelligence at RAF Medmenham during the Second World War, I was intrigued. Based on a sample chapter available online, I realised that it wasn’t the kind of novel I’d usually read (such as this, this and this; thanks for asking). However, what I was interested in was the use of the source material. As it turned out, there were no First Light “Stop! That’s not right!” moments while reading it. Instead, aside from the occasional transatlantic slip (for example, Tower Bridge and London Bridge are actually very different structures), the main problem I had was with seeing the (to me) familiar and well-documented words and actions of real people being given to fictitious characters.

The story, written by Canadian author Elinor Florence, concerns the young Rose Joliffe. When we first meet her in smalltown rural Canada in the summer of 1939, she is not long out of school and working for the local newspaper as the sole employee of the proprietor, a grumpy Scot called Jock McTavish. Once war starts, and eager to do her bit for the mother country (no, she’s not French Canadian), Rose finds her way across the Atlantic to enlist and after a few adventures, ends up involved in air photo intelligence at Medmenham. We follow her throughout the war and eventually (and this isn’t really a spoiler – Rose narrates so obviously she survives) back to Canada.

Plentiful research has gone into the book, the available published material supplemented with interviews and a visit to the UK to see Medmenham itself and other places, while descriptions of the experience of stereoscopic viewing suggest that the author has had a go at this too. Of the key sources though, only Constance Babington Smith’s Evidence in Camera is mentioned specifically. However, episodes from other books appear, such as Ursula Powys-Lybbe’s The Eye of Intelligence, in which occurs the idea of distinguishing cows from bulls on the basis of the shadows they cast (you would need very low, clear sunlight). Events, some major, some minor, from these and other sources crop up in the narrative, as Rose finds herself involved in the work undertaken in reality by Constance, Ursula and others. On one occasion, Rose – as narrator – offers us some words originally from Antoine de St Exupéry.

Now, knowing that knocking back the brandy after repeated blood transfusions isn’t a good idea doesn’t stop me from enjoying Bram Stoker’s Dracula [iii]; likewise, realising that the armadillo is not native to Transylvania doesn’t detract from the pleasures of Tod Browning’s classic 1931 film version. In fact, after a few viewings, you take their presence for granted and even look forward to them showing up. However, seeing the thoughts of Saint-Exupéry being uttered by Rose Joliffe [iv] was somewhat distracting, although if I were ever to read the book again, perhaps passages like that one might seem a little less jarring, much like those Transylvanian armadillos.

Genuine Transylvanian armadillos scurrying in the gloom of Dracula’s castle.

[i] I could have removed the earlier irrelevant reference to camping at Carnac; instead, I’ve chosen to leave it in and make use of it.

[ii] Renoir flew as a reconnaissance pilot in the First World War.

[iii] Nor, of course, does knowing that vampires aren’t real.

[iv] Flight To Arras, from which Rose’s words are borrowed, was first published in June of 1942, as well as being adapted for radio broadcast by the BBC Home Service later the same year.

Trackbacks